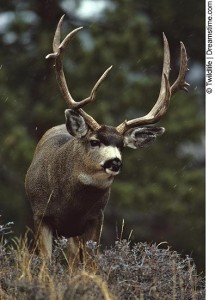

Modern Mule Deer Part 2: Adaptation and Evolution

Deer use the other forest creatures as sentinels as well. As you travel through the woods you’ll notice that squirrels, chipmunks, and all kinds of birds will call out to announce your presence. They do this unwittingly to announce danger to their own species, but in effect, also announce danger to the deer. I’ve observed these creatures doing the same thing to deer and elk, which can sometimes be useful to a hunter. But when the creatures bark at you, the deer always take notice. Next time you’re watching a deer, notice how it perks up its ears at every squirrel bark and bird chirp.

These are just some of my recent observations. In truth, mule deer have been changing continually—even dramatically—over the course of the last few decades. Anyone who spends a little time observing mule deer in the wild will witness all manner of well-thought-out security measures developed to avoid predators of all kinds; particularly the human kind.

Avoiding bowhunters is easy enough for any deer, but with today’s long-range guns shooting well over 1000 unethical yards, deer must adapt quicker than ever before. One way bucks have avoided rifle hunters for decades is to keep trees and brush between the hunter and himself. Older bucks are fully aware of the capabilities of long range weapons. Generally, if you bust a buck at close distance, he won’t run directly away from you but rather heads to the nearest tree, and then bee-lines away, careful to keep as many trees between you and him. If there are multiple trees or bushes, the buck will even zigzag from one tree to the next so the hunter never gets a shot.

One of today’s greatest mule deer hunting experts is author and speaker, Jim Collyer. In his book, Blood in the Tracks: A Mule Deer Manifesto (highly recommended reading by the way), he writes about an interesting encounter with very wise buck:

…I was working my way up a remote ridge and spied a good buck looking down at me from his bed on the ledge above. I could see only his head and the top of his back. I rested the rifle in the crotch of a tree and waited for him to stand up. Instead of standing, the wise old buck lowered his head and crawled on his belly (much the same way a dog does) until he reached cover. Then he uncoiled like a spring and bounced over the ridge, keeping as much brush between us as possible. While uncommon, I have seen bucks belly crawling twice and have talked with several other hunters who have witnessed the same phenomenon. Now, that’s smart! (Collyer 2013)

For as long as we have hunted deer, deer have developed ways to avoid us. It’s well known that deer are crepuscular animals (being most active at morning and evening). But in high pressured areas, I’ve seen deer become completely nocturnal; never rising during daylight hours. For the bowhunter, setting the alarm for 5 a.m. is almost useless because the deer have already fed, watered, and traveled to hidden bedding areas by starlight. Now, there are many degrees of nocturnal-ness. All deer feed at night, but if left undisturbed they also feed during the day. But as hunting pressure increases, deer become less and less daytime active—maybe rising out of bed for only a minute or two to eat and use the restroom before bedding back down again. Traditionally, mule deer experts have agreed that all deer must rise out of their beds to feed occasionally throughout the day in order to maintain adequate energy levels and fat stores. However, it’s been my observation that bucks living on high-pressured public lands have simply adapted to a nocturnal lifestyle which provides plenty enough food ingestion at nighttime to negate daytime feeding. It’s like saying humans have to eat occasionally during the night to survive. It’s just not necessary.

The following is a quote from mule deer expert and writer, Walt Prothero, concerning the ways mule deer have adapted to increased hunting pressure:

But mule deer are quick learners and highly adaptable…The bucks that didn’t pause to watch their backtrail survived to do most of the breeding and pass on genes that made them more secretive. Buck’s have essentially become nocturnal, at least during hunting seasons. They don’t pause in the open during daylight hours, and they won’t even come out in the open unless it’s dark. Most won’t move unless they’re certain they’ve been located. (Prothero, 2002)