Edge of perfection: My First Bull Elk

After nearly two hours of coaxing the massive bull elk in, exchanging bugles and blowing cow calls, he’s finally within bow range. But as I raise my bow ever so slightly, he catches my movement and whirls away. The charade is up. I’m busted; but I don’t care. Just to be part of such an exciting experience up here in the High Uinta Mountains has been worth it. Desperately, I blast another cow call. The bull stops and looks back in my direction. It’s not over yet…

It all started a year ago when my brother, Brent, and I hunted this area for a week with hardly a response from the nearly nonexistent elk. On the last day of that hunt I jumped over to the next drainage where I found myself literally surrounded by elk. Unfortunately, it got dark before I could get a shot. But it gave us hope for next year—actually, it gave Brent hope. As for me, I realized long ago that the only way to avoid a disappointing elk hunt was to stay home.

For fifteen years I felt detached from the prospect of actually shooting a bull. In the years that deer came easily, elk remained ghosts in the woods that I hardly ever saw. A great chasm had grown between me and the majestic elk. Seeing their caricatures in magazines, artwork, and free mailing labels never connected with me.

Just getting away from work and my relentless projects was nearly impossible this year. As the hunt drew near, I worked seventeen hours a day just so I could get away for five days. On Monday morning I finally managed to escape the cold, steely claws of responsibility, and literally ran out the door to my awaiting 4×4.

Three hours later, I was standing on the side of the worst dirt road I ever saw, watching my rear tire deflate in front of me. Suddenly a truck came ambling over the hill; lo and behold, it was brother Brent. He climbed out of his truck wearing an ear-to-ear grin that only a successful elk hunter could wear. While loading my tire with Fix-a-Flat, Brent recounted the exciting details of his hunt and how he was able to call his bull in for a fifty-five yard shot.

At that moment, any rivalry we had about “who’s the better hunter?” was gone. I was just glad somebody finally nailed down a branch-antlered elk after twenty years of hard hunting. I was honestly very proud of him, however, as I prepped my pack to head into the hills, I turned and said half-jokingly, “Well, I’ll just have to find a bigger one!” He replied, “Do it!”

Three and a half miles up the mountain I’ve located two bright yellow tents hidden in the trees: my new home for the week. It appears no one’s home, but I let out a little “locater bugle” just in case. My other brother, Russell, suddenly jumps out of his tent with bow in hand, and I laugh. He’s seen so much action up to this point, that he’s sure a bull has just wandered into camp.

We have about two hours of good light, so after catching me up on all his recent elk encounters, we head off to a nearby meadow. The evening falls quickly, and as expected we get no response from our calling. I sleep well that night with nary a vision of antlers dancing in my head.

5 a.m. comes way too soon, but I’m ready. Bowhunting is what I practice year-round for—it’s what I live for. We head out in the dark up a steep and rocky trail leading to a large meadow a mile away. This is where we’ll begin our first “set-up.” Our typical set-up goes something like this: Russ and I sit down about 50 yards apart and begin a series of cow-mew calls to imitate a herd of elk. After a minute, one of us lets out a series of estrus (cow in heat) calls followed by a lone bugle. Then we wait for a response. We repeat this process every five minutes for up to forty-five minutes. Then, as is usually the case, we look at each other in disappointment and try again somewhere else. This set-up is no different.

Farther up the mountain, we do our second set-up and again, there’s no response. Now this is the elk hunting I’m used to, and I’m thinking this trip will be just like all the rest…whoo-hoo! Most years, I’m cold and shivering half-way through the first routine, but this morning is surprisingly warm, even at 9000 feet. This will likely force the elk to bed down early and probably hurt our odds. Again, I prepare for disappointment.

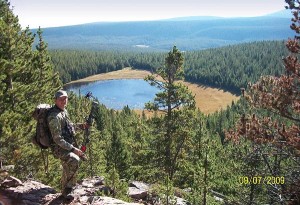

By disappointment, I’m purely talking about my yearly lack of elk steaks and back-straps that a lowly artist needs in order to survive the winter. Don’t get me wrong, every minute spent traipsing through Utah’s gorgeous backcountry is savored. It’s what keeps me coming back each year, even after eating “tag soup.” I love the smell of the woods, the truly fresh air, and especially the quietness. I love sitting beneath the lodge pole pines that reach forever upward towards the clear skies, bald peaks, and fast moving clouds. There are pinkish rocks and boulders strewn everywhere, which provide a quiet foothold on an otherwise crunchy, pine-needled forest floor.

I love watching all the wildlife too: the moose, the deer, the odd high-altitude birds with their strange songs, and even the annoying squirrels and chipmunks that jump from branch, barking at us for invading their territory. They’re all here with the elk, living together in harmony. I soak it all in, becoming happily alienated from the contrived reality back in the city.

A little while later we’ve arrived at Chuckles Point. It’s a high mountain point named by Brent who once got a great response from a bull he affectionately named Chuckles because of its distinctive bugle that ended with a series of chuckle-laughs, as if to mock his efforts.

There’s fresh elk sign here, so we get set up again. This time, halfway through the routine we get a clear return bugle. Game on! Suddenly I remember what I’m doing up here. Russ and I alter our routine with a series of cow calls to draw him in. The wise old bull is interested, but hangs up and refuses to come closer. Each return bugle becomes quieter, indicating that he’s moving farther away. If we cows aren’t coming to him, he’s not coming to us. Eventually, the bull is gone.

It doesn’t help that each time we set up, the wind changes—swirling one way, then the other. As luck would have it, the wind continues to shift like this all day. Later, when the wind has driven Russ completely nuts, I tell him, “Who cares [how we set up], the wind is just gonna change anyway…” But being a newbie to the elk hunting arts, he still has hope, which I find amusing.

Our next three set-ups are uneventful as we manage only an occasional, far-off call back. It’s 3:30 p.m. now; it’s hot and we’re exhausted. It’s nap time. My dusty day pack makes for a fine pillow; the thick pine-needled ground makes for a soft bed. At this elevation dreams are strange:

A giant bull appears at twenty yards, but as I draw back for an easy shot, I notice an old woman riding atop the beast like a horse. She’s okay with me shooting though, and moves her leg so I don’t hit her…

The sun is dropping and shadows are getting long; it’s wakeup time. Russ and I make our way to Rub City, so-named for the abundance of trees rubbed and thrashed by mighty elk antlers over the years. When the elk are in this drainage, this is their bedroom; it’s where they live and rest during the day.

To begin our routine, I split off from Russ and head uphill. Thirty yards uphill, I am surprised by an explosion of animals as a group of bedded elk jump to their feet and go crashing through the timber. I make an immediate cow call which stops one large cow at forty yards. She stands there staring back, but then the wind swirls. Just as Russ catches up, the cow lets out a strange alarm bark and trots away. It’s exciting to actually see elk, but at the same time I’m disappointed that we busted them. Well, that’s elk hunting. This has actually been the most exciting elk day ever; we actually saw and heard elk, which is truly special.

It’s around 6 p.m. now, and we have time for maybe one or two set-ups before dark. We finally arrive at our destination: the far eastern end of a large meadow we call Eight-Cow Meadow. It’s a secluded east-to-west meadow, very long and oval-shaped, widening to about 200 yards at the middle. Russ and I set up fifty yards apart at the edge of the tree line in hopes of drawing an elk across the meadow from the opposite wooded side.

Our call routine goes on and on and eventually my ears can no longer take the barrage of squeaks and squeals from the loud calls. I love quietness in the woods and this grand cacophony is the thing I hate most about elk hunting. Annoyed, I proceed to stuff wads of toilet paper into my ears.

So here I am sitting flat on my butt with my bow lying on the ground, and after forty-five minutes of calling, I’m looking back towards Russ and wondering when we can finally surrender to the empty woods. As I finish yet another routine bugle, suddenly BOOM, a big nasty bull screams at us from the left. In one fluid motion I hop to my knees, snatch up my bow, knock an arrow, and swing around to face the noise. He’s close and should erupt from the woods at any second. All senses are on high alert and my first thought is, the wind is bad, blowing steadily in the bull’s direction; he’ll surely blow out of here.

A minute later, everything is still quiet. Our eyes are transfixed on the thick woods. The bull has hung up and is silent, staring back at us and listening. We have to do something quick or he’ll leave. Russ blows a couple estrus calls, and I let out a small bull bugle. Since the bugle got him to respond in the first place—and since he sounds like a big bull—he’ll probably be happy to fight off a smaller bull for some cows. Another minute passes. Then suddenly, the same throaty bellow shatters the air; same distance, different direction. It sounds as if he’s circled around to the trees on the opposite side of the meadow. Russ scrambles over to me as we try to figure out exactly where the bugle came from. I’m certain that it came from the opposite side of the meadow, but Russ thinks it might be behind us…but he’s not sure.

We decide to sprint across the meadow to close some distance and try to draw him down from the trees above. Russ offers to do the calling while I sneak up into the steep woods to intercept the bull. Not gonna happen. As I go sneaking into the woods, we get the same bugle and chuckle, only now it’s coming from the side of the meadow we were just on! It occurs to me that the bull was actually behind us (as Russell previously thought) and his bugle was reflecting off of the wall of trees across the meadow (where we are now). In other words, we’re on the wrong side. Oh well, we’re here now, and in a millisecond my role changes from hunter to caller in hopes of drawing the bull back across the meadow towards Russell who’s waiting at the meadow’s edge.

I am completely energized, certain I can coax the bull in to the shooter. I run farther up into the dark woods and make more calls. I want to make the big bull think I’m a little bull running off with the cows. The bull keeps responding to my calls, but the farther I go up the mountain, the more distant his bugle sounds. He knows something isn’t right and isn’t coming any closer—smart bull.

I blow more calls, then grab a tree branch and begin smashing the limbs off a dead tree, attempting to mimic a frustrated bull tearing up a tree with his antlers. Next, I grab a bunch of large rocks and roll them down the hill to mimic hoof sounds. There’s no hesitation; this craziness is absolutely necessary to convince the bull that I’m a herd of elk. But all remains quiet, and I’m afraid he’s not buying it.

BOOM, anther bugle sounds, only now it’s coming from farther up the meadow. The bull has outsmarted us and is moving away, skirting just inside the tree line on the opposite side of the meadow. I run through the trees on my side, paralleling his movements and stopping occasionally to make cow calls. His response is becoming less frequent. I have no idea where Russ is at this point, so it’s every hunter for himself. Russ tells me later how he crossed back to the bull’s side of the meadow in attempt to close some distance.

At mid-meadow I’ve managed to mirror the bull’s movements according to his calls. The sun has dropped behind the mountain and darkness looms. My chances of ever seeing the bull are shrinking by the minute. Oh well, the excitement thus far is more than you could ask for. But it’s not over yet; I blow more calls, break more sticks, and roll more rocks. The next bugle is very loud and much closer. I can’t believe it; the bull has actually entered the meadow and is coming my way! Quickly I descend towards the meadow edge. Fifty yards from the meadow, another bugle erupts and I freeze. Through an opening I see a massive, tan elk body and dark antlers moving towards me. My eyes widen, my heart races. I don’t have to count tines. This is a wily old herd bull—a real monarch.

At the edge of the meadow there’s a giant pine tree that I can keep between me and the bull. When I get there, I crouch behind the massive trunk and mess of lower branches. From this vantage I can see not one, but two elk; the big noisy bugle-boy and a smaller elk (probably a cow) holed up on the opposite side of the meadow. The bull is walking back and forth in the middle of the meadow.

I hear Russell’s estrus cow call farther down-meadow and I’m relieved. It keeps the wary bull interested and distracts him from his even warier cow. The big bull turns and walks towards Russ, then changes his mind and walks back towards the cow. I take a yardage measurement: 114 yards away, twice the distance I need for a clean shot. To make things worse, the cow turns and trots back to the trees with the big bull following behind. He’s about to exit the meadow altogether and in ten minutes my sight pins go dark.

Pointing my elk calls toward the forest behind me, I start making desperate cow calls. The bull pauses, looks in my direction, then slowly turns and begins zigzagging towards me. He’s in no hurry and keeps stopping to look around. When he stops, I let out a call: estrus, bugle, mew, bugle, mew, estrus—whatever keeps him coming. This intense game of cat and mouse is working! Half-way across the meadow he lowers his head and tears at the ground with his giant rack, ripping up grass and mud and tossing it in the air. Frustrated and ready to fight, he keeps coming steadily to my calls. He’s almost within bow range now. Kneeling behind the big pine tree, I’m frozen like a statue with one crazy eyeball peeking through the branches.

After nearly two hours of calling I’m once again focused and calm. Closer and closer the bull comes, staring right through me. I can’t range him; I can’t even move. His head goes down and my rangefinder goes up. It reads 40 yards exactly. But as I raise my bow ever so slightly, he catches the movement, jumps, and whirls away. The charade is up; I’m busted! Desperately I blast another cow call from my Hoochie-Mama. He stops and looks back. Unsure of what I am, he veers left and starts quartering away quickly. It’s now or never. I figure he’ll probably see me draw my bow, but it’s my only chance. The sight pins scroll over his ribs, 20, 30, 40, 50; 50 yards is about right. Through a little twelve-inch opening in the branches, my arrow is off, streaking through the growing darkness.

THUMP. A strange sound rings out and the elk takes off trotting through the meadow. I didn’t see where my arrow went, but it sounded like a hit. Immediately, I blow a couple shaky estrus calls. The bull slows down and glances back at me occasionally as he continues away. Did I miss? About eighty yards into the meadow the bull suddenly jumps to his right like he’s losing balance, takes two more steps and just tips over. A weird cloud of surrealism washes over me. When I see that he’s not getting up, I burst from my cover and run into the meadow yelling, “HE’S DOWN! HE’S DOWN!”

Russ yells back from across the meadow, “WHAT?”

“HE’S DOWN! I GOT HIM!”

Russ appears running through the meadow towards me. “WHERE?” he shouts.

“Right there in the middle of the meadow; that’s him,” I say, pointing to a light colored pile sticking up out of the grass.

We exchange a very excited high-five and begin poring over a myriad of questions, trying to make sense of the last two hours. As we approach the mighty beast, I’m still in a daze. Russ begins counting tines, “Five-by-six,” he says. I have to reach out and touch one of the massive antlers to convince myself it’s real—but it doesn’t work. This situation, the intensity, the timing, the sheer lethality of a perfectly placed shot—the whole event is unquantifiable. There’s no way to ground my thoughts and feelings in an impossible situation that I don’t even trust. I give Russ my camera for documentary reasons, like when you see a UFO or Sasquatch. It’s not until I sit upon the bull’s massive body and feel its warmth in the cold night air that I feel a connection with reality again.

The arrow hit just behind the last rib, angled perfectly through the vitals, and lodged in the opposite front shoulder just under the hide. An absolutely perfectly placed arrow at fifty yards adds even greater mystery to a perfect hunt that still perplexes me today. Admittedly, I am a decent shot, but under that kind of pressure, not to mention shooting through tree branches and low light, maybe I was just lucky. To my credit, I think my year-long practice paid off. Too many botched shots on the previous year’s deer hunt caused me to obsess over shot placement all year long. And in the process of refining my skills, archery evolved from a fun hobby-sport to a way of life.

As we quartered the animal out by headlamp, I mentioned to Russ that this hunt had happened on a razor’s edge of perfection. It couldn’t have happened any other way; there were just too many variables. For example, a week-and-a-half earlier I had taken a perfect, fifty-yard broadside shot at a deer and missed wildly, only to learn that my new broadheads flew erratically outside of thirty yards. Thus, I replaced them right before this hunt. On that same hunt, I put a stalk on a small bull and was ready to take a forty yard shot when the wind changed and blew the herd out. Had the wind been different just a week earlier, none of this would have happened.

Special thanks are in order to the following people who made this hunt possible: Mom and Dad for packing the meat off the mountain, Brent for letting me use all his fancy camping gear, and Russell for all the extra elk calling, water filtering, meat hanging, and BS’ing. Unlike deer hunting, elk hunting is a great opportunity to spend quality time with family and friends in the great outdoors.