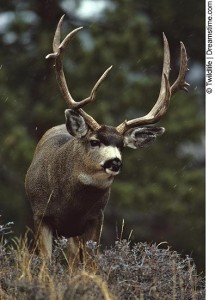

Deer Hunting Story: One Giant Antler

There is an image, not unlike the one above, that still haunts me today.

It was the muzzleloader hunt of 2001. I was still getting used to my new hunting area near Fairview, Utah. I knew the hunting pressure would keep the big bucks in the thick timber, so that’s where I spent my days. I’d never gotten a real trophy-size buck before, and up until then, I’d only seen a few true trophies in all my years of hunting. But I’d seen enough in this unit to know it was possible. These were the bucks I daydreamed about.

On opening morning our camp dispersed across the land. I dropped into the deep and steep pine forest below camp. The deadfall was so thick I had to hop from log to log, not touching the ground for a hundred yards or so. Eventually it opened up with aspens and narrow feeding swathes. Judging by the sign—and I was no expert back then—there were plenty of deer around, but where they went during the day, no one knew.

I’d grown accustom to blowing stalks on large deer, and as you’ll see, my confidence was way down. I knew there were big deer in this unit, attested to by an occasional flash of antler, a loud snort, and the sound of heavy hooves smashing away through the dense woods. I pressed on, but really, I’d already given up.

Judging by the high sun, it must have been close to noon. I knew the deer wouldn’t be up on their feet at midday, but I wouldn’t allow myself to return to camp and make excuses for my failure; blaming the lack of deer on the area and then bedding down for the day myself. That would be submission. No, I would continue my quest, beating the pine-needled forest floor to death with my stinky old boots.

I was still-hunting along on a steep and rocky slope. The timber was less dense at the edge of the pines where interspersed aspens and deer brush heedlessly begged for a more sun. My predator eyes suddenly and haphazardly caught the slightest bit movement a hundred yards below me in some tall brush. My cheap, murky binos came up and locked on. ANTLERS! Little bits of tines bounced and bobbed through the tall brush. What they were attached to I could not tell in the thick brush; no fur nor face nor hide nor hair, just bits of antlers appearing and disappearing. How big was he, I wondered? A two-point? A four-point? No way to tell and no shot; I needed to get closer.

Here’s where my lack of confidence shines brightest. Based on previous buck encounters, I told myself this would never work out. I didn’t really believe I could get close enough for a shot, but I had to try—I desperately had to try!

It’s different these days, here in the future. Today, I would just sit tight. The wind was most likely rising from late-morning thermals. I would sit and wait for the buck to feed into the open, even if it took all day. 100 yards is an easy shot with a gun. Woulda-coulda-shoulda. But this is how we learn…

I dropped to my butt and began my slow-motion descent. The pine needles were dry and loud, and the terrain was terribly steep. I used the wind and forest sounds to cover my approach. For twenty minutes I slid, scooted, and crab-crawled down the hill, drawing closer and closer to the sighting. Minutes felt like hours.

The buck eventually moved out of sight, swallowed up by the forest. Unable to keep tabs on him, I became increasingly skeptical. Did he bed down? Did he sense me and move off? Gotta get closer! I crept closer and closer until I was within a few yards of where I first saw him. All was quiet. Now what?

He’s gone! I must have busted him out. I knew this would happen. Oh well… I would’ve been a little upset if I ever truly believed I had a chance at this buck.

I stood up, slung the gun on my shoulder, and dug my GPS unit out of my pocket. I stared blankly at the screen as it tracked and tracked and tracked for satellites. There’s nothing more tedious than waiting for the GPS to track in thick timber. My eyes lifted and floated around the forest. What direction did he go, I wondered.

As my gaze drifted to the right, my lethargic eyelids suddenly flashed wide-open; my heart stopped. Fifteen yards away, a massive, tall, sweeping, 4-point antler stuck directly out from behind a large tree trunk. On the other side, the long gray line of a deer’s back extended outward.

No thoughts, just action.

In one motion my left hand opened and the GPS went into free-fall. My hand flashed to the butt of my gun. The GPS was halfway to the ground as my gun twirled like a baton in front of me. My right hand caught the gunstock and lifted it to my shoulder. The GPS bounced inaudibly as the gun’s muzzle swung towards the buck.

Too late. Heavy hooves dug into the ground with a loud thud and every trace of that monster buck instantly vanished into the woods. Frantically I aimed at the crashing and snorting of my invisible foe, but he was gone.

And that was that. Nothing left but a haunting technicolor image of a huge antler sticking straight out of a tree trunk, burned forever in the forefront of my long-term memory. For the duration of the hunt I beat myself up for my failure.

I am tempted to leave the story right there, but habit forces me find the good in the bad. I knew then, as I know now, that my biggest mistake was over-estimating the buck, and under-estimating myself. I failed because I accepted failure from the start. I had him in my hands, if only I’d been patient. If only I had believed this one burning truth: that he was “just a deer” and not an impossible phantom.

The End.