Top 3 Tips to Improve Your Archery

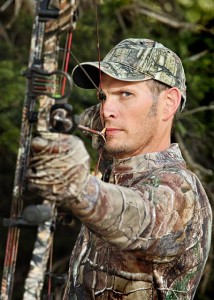

Now that spring is here, you’ve probably taken your bow out, dusted it off, and sent some arrows downrange. Maybe some were bulls-eyes while some were errant, but it’s early yet and there’s always room for improvement.

In the last ten years I’ve worked tirelessly at becoming a better hunter. But at the same time, I’ve also developed some bad habits. These habits are common to most archers and include punching the release and lack of follow-through. What you do at the end of your release has the greatest effect on accuracy. So in today’s lesson we’re going to relearn how to shoot.

Bad shooting habits develop because we’re too focused on hitting the bullseye. Everyone knows that humans can only focus on one thing at a time. Ironically, if we focus too hard on the bullseye, we’ll actually miss it!

Here’s the fix

- RELAX!: A famous target archer once said, “A relaxed mind cannot exist in a tense body, and a tense mind cannot exist in a relaxed body.” More than anything else, the bow and arrow fights relaxation. First, there’s the mental stress of hitting the bullseye, especially in a hunting or competition. Second, when you draw your bow, your whole body becomes physically tense as it struggles to crank back and hold all that weight. So, now your mind and body are under duress. Your fight and flight response takes over and all that matters in the world is getting rid of that arrow. Now STOP! Tell yourself you will not release until you calm down. Breathe in and out a couple times. Put your sight pin on the bullseye, then take it off, and put it back on again. Who cares if you miss? Refuse to shoot until you are completely calm. Eventually this will become habit and will have the greatest effect on your accuracy.

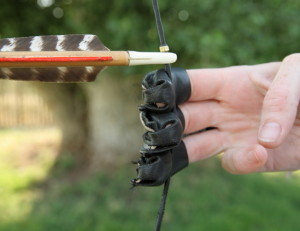

- The Open Grip: By now you probably know how to grip your bow, but it’s worth another look. First, your bow’s grip should begin at U-shape between your thumb and index finger. Second, your grip should contact your hand along your life line (the line that separates the fleshy part of your thumb and middle of your palm. Third, the grip should end at the center of your palm where your wrist begins. If you do this correctly, the middle knuckles of your bow hand will form a 45-degree angle slanted away from your grip. NOW, this is only the beginning. When you draw your bow, your fingers should be relaxed and open away from the bow’s grip. Your fingers should remain relaxed throughout the entire shot. The best way to do this is to make an “okay” sign with your index finger and thumb lightly touching. Your hand must remain like this throughout the entire shot.

- Follow-Through: Seems simple, right?! It’s not. Again, you can only focus on one thing, so if you’re still aiming at this point, then you’re not following through. Aiming should go as far as letting the pin float tiny circles around the bullseye. At that point, your only focus should be on pushing the bow forward with your bow arm, and steadily pulling the string back with your release hand. The pin floats almost subconsciously while your focus floats freely and relaxedly between back tension, breathing, and oblivion. Oblivion is where you are free of all anticipation, free of all tension, and free of all distraction. All the technicalities of archery have become one simple action (form) and relegated to your subconscious mind. With nothing left to distract you, you are free; you are in the moment, perfectly centered between the future and the past.

The goal of archery is to relax: relax your grip, relax your body, and relax your mind. At this point, the bow is loosed on its own terms. The bow-and-arrow is accurate every time, subject only to the laws of nature which are fixed. The only variable is the shooter. The greatest obstacle YOU and how you influence the shot. When can master yourself, you will experience perfect archery with every shot.

Note: I’ve included a video in my next blog post that demonstrates the 3 steps to better archery. Here’s the Video Link.