How to Choose a Taxidermist

It’s often said that one should spend as much time researching taxidermists as they do researching their hunt. That’s because a taxidermy mount embodies the memory of your hunt for a lifetime. A quality mount is not cheap, but neither is your hunt. While your hunt will soon be over, the memories will remain. So isn’t it worth investing a little time and money in a quality mount? In this article I’ll guide you through the process of selecting a quality taxidermist.

Before we begin, I should mention that I’m a professional taxidermist living in Southern Utah. My business is Nate’s Taxidermy and I’ve been mounting big game animals for ten years. I’m not seeking to score more business with this article, but rather help fellow hunters figure out how to get professional quality mount.

One reason I became a taxidermist was the vast unprofessionalism I encountered in the industry before I became a taxidermist. Turnaround time was always delayed, craftsmanship was questionable, and professionalism was unheard of. Calls mostly went unanswered and any guarantee of quality was non-existent. With this in mind, here are my top suggestions for anyone searching for a taxidermist.

Quality of work

First off, visit as many taxidermy studios as possible. Every taxidermist should have a well-lit showroom with a variety of species to inspect. The goal of taxidermy is to bring the animal back to life…or close to. Do the specimens look “alive”?

Begin by asking what skills and methods separate them from their competition. When touring showrooms look for things like symmetry in the face, especially the eyes and ears. Watch for drumming (places where the skin has pulled free of the form). This usually occurs in highly detailed areas like the face, inside the ears, and around the legs. Drumming indicates low-quality glue or cutting corners.

Another place to inspect is antler bases. Make sure there aren’t any gaps or separations where the hair meets the horn. Also, take a close look at habitat bases. If you see something weird in your wanderings, ask about it. A real professional will be honest and friendly, and value you beyond the money you’re spending.

Turnaround Time

Unless you are in a big hurry with your mount, don’t base your decision solely on a fast turnaround time. That being said, your mount should be finished within a reasonable time, say 8 to 12 months. Good taxidermy takes some time, but not years.

Most high-volume taxidermists use commercial tanneries, which are better than in-house tanneries (in my opinion). But most commercial tanneries are currently 8 months out due to supply-chain and staffing issues. As of 2023 you can expect completion times can to be a little longer.

Once the hide is back from the tannery, it shouldn’t take more than a month or two to complete. If your taxidermist keeps extending the time he quoted, or making excuses—like blaming the tannery—then beware. A taxidermist who accepts too much workload is more likely to cut corners on your mount.

Quality of Materials

Most people would be hard-pressed to distinguish whether cheap materials and high quality ones were used in the final mount. But there is a difference. Just like a food recipe, the quality of the final product depends on the culmination of ingredients. It would behoove you to ask about various materials used.

Start with the tanning process. Was the hide professionally tanned, or just “dry preserved?” Dry preserved isn’t really tanning, and in my opinion should never be used since it will drastically decrease the shelf life of your mount.

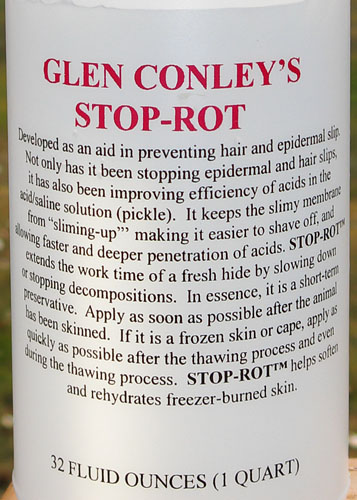

Next is the glue (aka hide paste). Hide paste is what holds the whole mount together. There are a variety of glues on the market, but many taxidermists are still using dextrin-based glue simply because it’s very inexpensive. Dextrin works, but it’s also a food derivative (from corn starch) which can attract bugs. Modern synthetic glue is much better. Some glues even contain bug-resistant additives.

Synthetic glues are more expensive, but they’re necessary for the long term survival of your mount. So be sure to ask about the glue! There are many other materials used as well–things like eyes, ear liners, paint, etc—but most are visibly apparent. Basically, if the mount looks cheap, it probably is.

Professionalism and Paperwork

Anyone working in the dead animal business is gonna be a little strange (myself included). Still, no business can survive without some basic customer service skills. Why should taxidermy be any different?

Let’s start by answering the phone. Simple, right? Nope. I recently tried to call a fellow taxidermist for a month straight before giving up. Apparently it’s still a problem in our industry. If your taxidermist does answer the phone, is he courteous and helpful?

What about paperwork? In the past I was given a little, scribbled receipt showing little more than my deposit was paid. When I opened my own taxidermy business I started with the paperwork.

When a client brings me a project, they receive a signed agreement with various details including balance of account, turnaround time, guarantee of quality, desired mount position, and even measurements taken from the carcass. When they pick up their finished piece they receive a “care sheet” for the long-term maintenance of their mount.

Professionals should also have a decent website with updated photos, contact info, and other helpful information.

Clean and Orderly Workspace

When you visit the taxidermy shop, is it clean, orderly, and well lit? Or is dark, dingy, smelly and cluttered? Similar to a mechanic’s shop, working conditions often reflect in the quality of service. For example, taxidermy requires a myriad of specialized tools. How can a mount be done properly if the taxidermist can’t find the right tools?

Cleanliness is also vital in a shop. A sanitary workspace prevents insect infestations, as well as bacterial cross-contamination from one project to another. I once visited a shop with a huge bison skull rotting under a table. It smelled so bad I could hardly breathe. The taxidermist didn’t seem to notice, but it didn’t help my confidence any.

Specialization vs. Generalists

One of the first questions to ask a prospective taxidermist is which animals they specialize in. This can usually be discovered on their website, if they have one.

Some taxidermists are generalists while others are specialists. Some guys specialize in birds; others specialize in big game (myself included). There are also specialists in skulls, fish, African game, and small game.

A generalist does everything–fish, deer, skulls, etc. This is fine and dandy, but such a broad spectrum of work requires many more years of training and experience. African big game–which includes vastly more animals–is more specialized than North American big game and also requires more specialized training.

In the end, just make sure you’re not dropping a deer off at a fish guy with little experience in big game.

Experience and Training

Be sure to ask about experience and training. How many years has the taxidermist been in business? How many times has he mounted the specific animal you’re interested in? Where did he get his training from? Did he go to a specialized taxidermy school or was he trained as an assistant? Both are fine so long as he’s acquired the requisite foundation in his field of taxidermy.

Experience matters. Every animal and every animal manikin (form) is unique, and thus requires some level of customization. Only specialized training and experience will guarantee the accuracy of your mount.

Customer References

It’s a good idea to request a reference list of previous customer phone numbers from your prospective taxidermist. With a deer or duck you might be fine with just visiting his studio. But with an especially large or expensive mount (e.g. life-size grizzly bear, bison or musk ox) you’d be best making some calls.

A few key topics to discuss with past customers is turnaround time, customer service, and quality of their finished mount. I would also ask long-term customers how their mounts are holding up over the years, and whether or not they would use that taxidermist again.

Conclusion

That’s about it, folks. I know these are mostly common sense items, but you don’t want to take chances with your once-in-a-lifetime memories.

Taxidermy is as much an art as science. Science says your mount should accurately recreate the living creature. A good taxidermist will ‘bring the animal back to life.’

Art, on the other hand, is subjective. That’s where finding the right taxidermist with the right style comes into play. Style varies from artist to artist, so your goal should be to find the taxidermist who reflects both the “look” you desire and an accurate representation of your trophy.