Zen in Hunting Part 2

Trying to explain Zen to people has been difficult, not just for me, but for all Zen teachers, even the Japanese Zen-masters themselves. Reason being, the meaning of Zen is not something you can just tell someone, but rather something that must experienced.

In Western culture we expect things to be tangible and definable. But in Eastern culture some aren’t explained with words, but through experiences. If you were to ask a Zen-master to explain Zen, he’d likely turn his back on you. Zen is a sacred art, and not something to be handed out like candy. Its power is beyond mere words, even beyond the teacher’s full range of understanding. It is also something that should be earned through hard work, humility, and sacrifice.

If you haven’t read the epic novel, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, you should probably be deported. It’s an important and powerful Western perspective of Zen. It also predicts the downfall of Western civilization via our own greed and self-centered worldly perspective. He goes on to explain that the Western business model will increasingly dictate our values in the near future. The fallacy of the Western business model is this: If a thing or idea cannot be quantified, monetized, or assigned a tangible value, then it must be dismissed. Why do you think society hates religion now more than ever before?

Like it or not, this bias is the driving force behind all decisions regarding Western business, values, morality, emotions, decisions, relationships, the stock market, the government, etc. Have you ever noticed that every elected official is a living pile of crap, and the “good guy” politician always loses and no one knows why? He loses because his truth and his goodness can’t be quantified. The dirt bag politician, on the other hand, wins because he tells so many lies, and lies are data which can be added up and quantified. So he wins by numbers. But I digress.

Pirsig was a great prognosticator. He understood that the Western business model would inevitably lead to our destruction. He foresaw it very clearly, but felt so helpless in preventing it that it drove him certifiably insane.

What proved Pirsig’s theory was simple: The word QUALITY is indefinable in Western culture. Everyone he asked seemed to have only some vague idea of what Quality is, but they couldn’t really define it. That’s because Quality can’t be defined. Quality can’t stand on its own. Quality is only useful for comparing two objects. For example, this toothbrush is better than that toothbrush, so this one is a quality toothbrush.

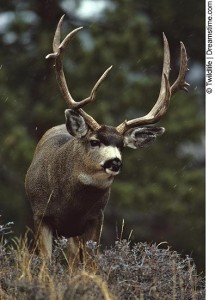

Quality is very similar to Zen insomuch as it’s something to be experienced, not explained. You know when you have a quality experience–like shooting a giant buck or watching your son being born–but trying to explain why it’s a quality experience is impossible without comparing it to something lesser. And since it can’t be defined, it’s often discarded by our culture. Now, more than ever, it’s easy to see what Pirsig predicted 40 years ago is coming true: quantity over quality in all things. Don’t believe me? Just look at Walmart!

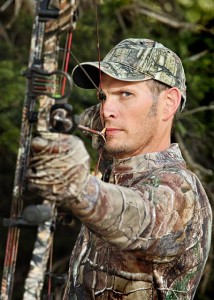

Before we continue, I want to make it clear that I am not a Zen-master; not even close! I’m only a traveler along the Great Path. I only happened upon Zen because of the meditative rituals that I experienced while hunting. At the same time, I believe that the purpose of life is to follow the one true path, and that is the path leading to enlightenment. If I have any understanding of Zen, it’s only because I’ve traveled farther along the path than most. And if this is true, then I can help others.

Are you seeking Zen in your life, or are other forces (dogmas, hope, ignorance, etc.) guiding you? Can the ancient art of Zen really be used for hunting? Is God and Zen really the same thing? These are all questions that I ponder every day and hope to answer in future posts.

As of now, we’ve only scratched the surface. For the final piece of the puzzle, see…